Respected as a beef cattle expert, William Collins intended to use Nindooinbah to fatten cattle for the frozen meat trade which he had helped to pioneer in the 1870s. He was also a co-founder of the North Australian Pastoral Company with his brother in law, Douglas Fraser, Sir Thomas McIlwraith and two other partners, and helped to establish wool sales in Bris-bane. Even though half of the run had been resumed under the 1868 Crown Lands Act, Nindooinbah was one of the larger properties in the Beaudesert region in 1900: Jimboomba 4,000 acres; Maroon, 7,000 acres; Tamrookum, 11,000 acres; The Hollow, 7,000 acres; Rathdowney, 22,000 acres; Nindooinbah, 19,000 acres; Undulla, 7,000 acres; Mundoolan, 12,000 acres; Tabragalba 19,000 acres; Tambourine, 5,000 acres, making a total of 141,000 acres held by 13 estates. William Barker held Tamrookum in 1854.

In 1900, William Collins married Gwendoline Roberts in Dune-din, New Zealand. In 1901 he offered to renew the lease of Nindooinbah from William Barker, Ernest White’s father in law and one of the trustees of his estate. At that Figure 6: 1900 photograph, view from the east time, Collins estimated the costs of necessary improvements and repairs at Nindooinbah to be £600-£700. Noting that the house was ‘out of repair’, needing a new kitchen and painting throughout, he suggested that wallpaper might be preferable to paint.

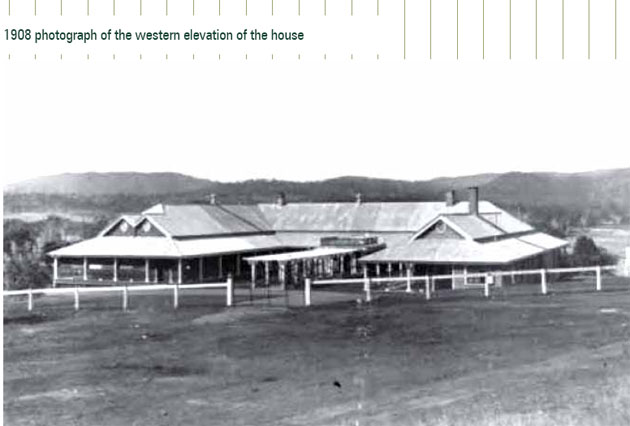

A new fence around the house and garden and ‘miles’ of property fencing were also needed. The garden was a ‘wilderness’; devoid of flowers. A photograph of Nindooinbah, published in Queensland Country Life in 1900, with an article written to boost the sale of the first set of dairy farms cut from Nindooinbah, shows a white picket fence close to the house, two chimneys, a narrow staircase; plantings close to house included two palms at the verandah corners and a large bunya pine close to location of the eventual southern extension.

[This photograph also shows another building with a high pitched roof at the rear. A 1905 photograph of the rear of the house shows this building, located close to the eventual kitchen wing, in more detail.]

In May 1901, William and Gwendoline Collins, then living at Mundoolun, visited Nindooinbah. In August 1901, they were at Nindooinbah ‘fixing up’ the house and unpacking the ‘English and Japanese boxes’ of treasures’.

Nindooinbah was sold to William Collins at auction on 7 May 1906. He paid 2835.16.6 pounds for a total of 497 ac or 16p on three separate titles. On the same day, 6092 acres divided into 26 dairy farms, were auctioned. These 26 farms were described as bordering ‘existing farms’.

Dairying expanded rapidly in southern Queensland in the first decade of the twentieth century. The location of the Logan-Albert region close to Brisbane sparked a dairying rush. Two butter factories had been established in the area by 1906, dairy farms excised from Tabragalba sold successfully in 1905, and the local papers reported that potential dairy farmers seeking land were growing impatient.

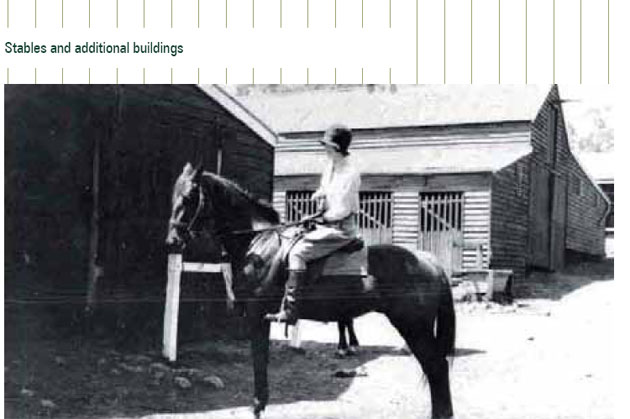

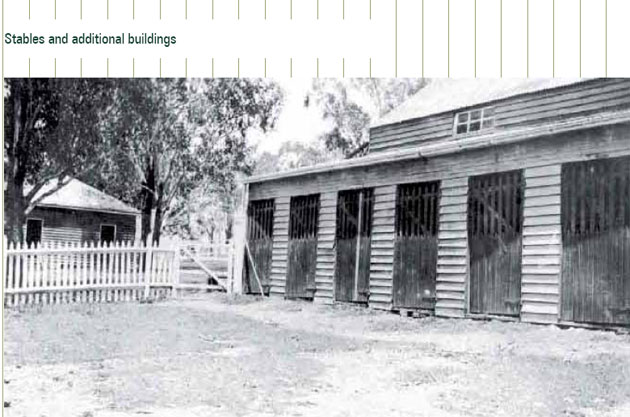

The Nindooinbah farming land was described at the time of the auction as having ‘all been ringbarked’ with numerous cattle camps and large trees remaining for shelter’. Seven dairy farms remained part of the Nindooinbah estate; the remnants of three of these farms are extant in 2005. William Collins embarked immediately on a programme of major development at Nindooinbah, on the property as well as at the main house.

Tenders were called to construct a cattle dip at Nindooinbah. Collins was closely connected to the battle against the cattle tick Boophilus microplus, which had been introduced to Australia with the importation of bos indicus cattle through the port of Darwin.

William Collins was one of the Queensland government commissioners who visited the United States to study Texas tick fever, and was co-author of a Queensland government report on tick fever in 189638. The Nindooinbah dip was completed in 1907.

Other features added at this time include large water storage tanks, mentioned as badly needed in Collins’ 1901 letter, and a gas house adjacent to the large detached laundry, presumably to provide power for, among other implements, gaslights installed circa 1913.

A building in the position of the present laundry is visible in a photograph circa 1908.

The architect Robin Dods was commissioned to prepare plans for an extension to the main house. This which more than doubled its size and established Nindooinbah’s status as the most distinguished homestead in the district, and one of the most important in Queensland.

In executing the extensions, Dods respected the plan of the 1857 house. Most rooms maintain the ‘one room’ depth of the house, the verandah detailing was continued on the new verandahs and additional sets of stairs, and the roofline was retained when the roof was reconstructed. The extension to the main eastern elevation and the new northern and southern wings converted the original L shape into a U shape, a design found in other important early homesteads, such as Talgai on the Darling Downs.

Like Talgai, the main entry to Nindooinbah was by a carriage drive to the rear of the house. The addition of an entry porch and pergola at the rear of Nindooinbah gives the impression that the house is E-shaped. The extensions to Nindooinbah are also very important in demonstrating the domestic hierarchies which operated in that era.

The four Collins children, born between 1901 and 1908, were accommodated with their nurse and governess in a ‘nursery wing’, adjacent to the original bedrooms on the northern side of the house, with gauzing on the verandahs providing protection against mosquitoes. This wing was completed with a bedroom and bathroom, always known as the ‘bachelor’s room’ where male guests were accommodated. A new ‘service wing’ on the southern side provided a new kitchen, utility rooms, staff dining rooms and smaller bedrooms for the staff.

The staff bedrooms at the end of the southern wing are not shown on Dods’ original plans, but a photograph taken when the work was newly completed shows that the southern wing was completed at the same time as the main extensions.

The original kitchen shown in the 1905 photograph was moved to provide additional staff accommodation on the property and appears to have formed the core of the present manager’s house.

Recycling usable buildings and fittings was common practice on pastoral properties and occurred several times at Nindooinbah, and as recently as the 1980s when a cottage located close to the manager’s house was moved to serve as an artist’s studio in a position commanding a view of the lagoon, the Albert River and the mountains beyond.

French doors from the 1858 house, which Dods replaced with wider French doors, appear to have been installed in both the manager’s house and the present studio, a factor which adds to their cultural heritage significance. The surviving specifications for the new work demonstrate that high quality materials were to be used throughout. Crows ash was specified for the floors of new wings, wider cedar French lights with top portion divided into 6 lights, bottom panelled and stock-moulded were specified to replace the narrower original French doors, and the verandah posts in the kitchen wing were to be ironbark with red Stringybark railings and cedar capmolds. The kitchen wing was to have T&G ceilings.

Fixtures in the kitchen included a towel roller to extend across the fireplace, a kitchen dresser, for which detailed specifications were provided, a pantry table and a glass fronted pantry cupboard. A long list of brass fittings was specified for the kitchen and bathrooms. The servant’s bath was to be capped with beech and the walls were to be papered.

The new dining room, adjacent to the original dining room/ entry hall is a fi ne example of Dods’ work. It is panelled in silky oak, installed without nails, which disguise cupboards in its southern wall. Dods’ specifications include tiles for the dining room chimney, but the preferred type and style of the tiles is not mentioned.

The decorative plaster ceiling includes a wreath over the eastern bay window with the date ‘1908’, said to have been preferred by Gwendoline Collins instead of the more usual stamp of the owner’s initials because she regarded ‘WC’ as unsuitable.

A small servery connecting the western wall to the back verandah close to the kitchen is remembered by family and guests as having been regarded as ‘extremely useful’ by successive owners. The extant furniture in the new guest bedroom believed to have been constructed from bunya pine from the tree shown in the 1900 photograph.

The main point of entry was separated from the western verandah by an entry porch with a parapet designed to echo the verandah pattern.4 inch concrete foundations were specified for the pergola walkway from the main drive to the porch. Entry through rear courtyards is found in many Victorian era homesteads, including Mundoolun and Coochin Coochin in the Beaudesert and nearby Boonah districts and Talgai, near Warwick. Dods specified crows ash entrance gates but these are not shown in a circa 1908 photograph.

The new work included renovations in the existing 1858 house. These included an extended drawing room mantle, a cedar mantelpiece in the main bedroom and electric bells with ornamental pushes. Dods also specified the quantity of wallpaper he anticipated would be needed in the renovated area and in the extension: 82 square yards of wallpaper friezes and 238 square yards of wallpaper. Wallpapers with decorative features are common in Edwardian houses, and it is likely that surviving wallpapers in the drawing room and guest room are the ones installed at this time, said to have been hand-blocked in London. Ceiling papers were also installed, although Dods had specified painted ceilings.

A great deal of attention in the specification was paid to bathrooms and lavatories. The ‘existing bath’ was to be ‘moved and refixed’ and fitted with a ‘plunge’ spray and shower bath with a waterproof curtain. A Doulton Simplicitus 300 E lavatory was also specified. Although two early lavatories are extant, neither are Doulton. The bathroom and lavatory arrangements indicate that the extensions at Nindooinbah were created with guests and entertaining in mind, as befits an eminent pastoral homestead. Two lavatories, with doorplates assigning one to women and the other the men, and a bathroom were installed at the far end of the main wing, separated from the main guest room by a corridor. The southern end of the back verandah was marked on Dods’ 1906 plans as a service hall, further confirming that the extensions to Nindooinbah were conceived as creating an elite house where entertaining would be a feature of life. In several respects, Dods’ 1906 plans and their accompanying specifications were not executed exactly as drawn. Extra rooms were added to the southern kitchen wing, so that in its length it is symmetrical with the northern nursery wing. At some later stage, the ‘serving hall’ was furnished with extensive built in bookshelves to create a library, which is shown in a 1920s photograph with a table and chairs under the southern windows.

The garden

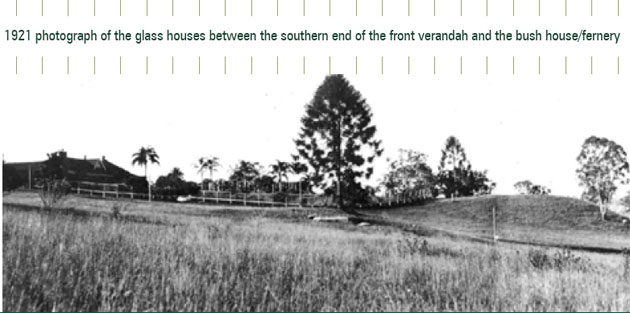

The garden was extensively developed during the Collins period. A photograph of the front of the house circa 1910 (See Figure 10) shows the main eastern elevation with an avenue of palms extending from the verandah towards the lagoon. It is likely that this avenue ended inside a fence enclosing the garden. A large round rose garden, shown developed to maturity in 1920s photographs, is not present in 1908, which may indicate that, if Dods had influenced the original layout of the garden and the palm avenue, his plan was modified by Mrs Collins who is known to have had a keen interest in the garden. It is not known whether earthenware pipes, believed to have been laid at Dods’ direction, remain under the extensive lawn area. Plantings of annuals inside the garden fence, smaller round gardens, new trees, extensive bush houses and glasshouses, no longer extant, made a labour intensive garden. At least four gardeners were employed at Nindooinbah. By 1911, Nindooinbah was ‘celebrated for its beautiful blooms’.