Nindooinbah as a whole

Nindooinbah in 2005 presents layers of use and occupation accumulated since the first pastoralists arrived in the 1840s and the first substantial house was built in 1858. This complex layering expresses successive owners’ perceptions of Nindooinbah’s standing, as well as their own needs, agricultural interests, tastes, awareness of prevailing fashions and standards, and financial position.

The present house represents a major work by R S Dods, of Brisbane architects Hall and Dods. When the Collins Company secured the freehold of the homestead block which included the 1858 homestead in 1906, Dods was consulted for a major expansion of the home. The Collins family knew Dods from his involvement with the Mundoolun Church built in 1901 and were donors to St John’s Cathedral where Dods was also involved. For the Robert Collins family he subsequently designed a chapel at ‘Tamrookum’ in 1913 and carried out additions to ‘Tamrookum’ homestead. The design for ‘Nindooinbah’ which was drawn in May 1906 used the old homestead in part and incorporated it into a much larger building. It is likely that the early homestead was intended to be larger and the scheme by Dods fulfilled this intention. The present telephone room, while it may have been used as a dining room in the past, was always intended to be a central hall to a larger house. Two early decorative schemes under the present wallpaper support this assumption, (Preliminary investigation of the interior finishes appear to support this assumption, however further investigation is required.

The big change Dods made to the homestead, was to put emphasis on the west side as the entry side whereas the earlier house had been entered in a conventional way from the east. In the new arrangement the east elevation became a garden front but the entry was then from the west, via a long pergola and porch placed centrally between a bedroom wing and a service wing on the north and south respectively. An earlier service (kitchen) wing, which was detached, was moved and was likely to have become the core of the present manager’s house.

The homestead was the largest domestic work designed by Dods, which was actually built. Its cost is not known but it is estimated it would have been more than £3,000. The records which pertain to the house include the working drawings and details as well as a specification and bill of quantities. This in itself is very rare and helps to interpret the work that was undertaken. The design was not typical of other designs by Dods for houses or homesteads. Unlike other domestic works it used many of the details of the old homestead such as the verandah posts and balustrade and replicated them so that the completed building had consistency. This may have been a request of its owners, or it may have been entirely Dods’ decision, but it was different to the approach used with other additions to houses, where the new work was very distinct from the old. With houses where additions were made, like ‘Callandar House’ for his brother Dr Espie Dods, or at ‘Glengariff’ for T C Beirne at Hendra, Dods did not try and match details of the original buildings.

The explanation may be simply that Dods liked the robust nature of the 1858 homestead and saw this as an opportunity to complete it. In any event he did make improvements to it such as replacing all the existing French lights with much wider (5’0”) openings to improve cross ventilation.

The early house was raised on stumps and this was a departure from the construction of other homesteads in the vicinity such as ‘Mundoolun’, which was also in the Collins ownership. The tradition, which dated from the 1840’s, had been to build on a foundation of logs lying horizontally on the ground rather than to use ‘blocks’ or ‘stumps’ projected vertically from the ground. The 1908 additions to ‘Nindooinbah’, while supported on stumps, appeared from the western side to sit low on the ground. The levels had been excavated and shaped to give it this setting, which concealed the stumps. This was consistent with Dods dislike of highset houses and his preference for connecting the house visually to the ground. On the garden elevation the space between the stumps was infilled with lattice in the manner of the 1858 house.

The external cladding of 12” chamfer boards was matched in the new work but a visible joint maintained to show where the old walls met new walls. Although not detailed on the drawings, much of the old house was reconstructed. Cedar had been used widely in its construction even to the rafters and the floorboards which were 1¼“ thick. The verandahs were replaced with crows-ash tongue and groove boards and the old verandah flooring in cedar was reused as lining boards within the roof space.

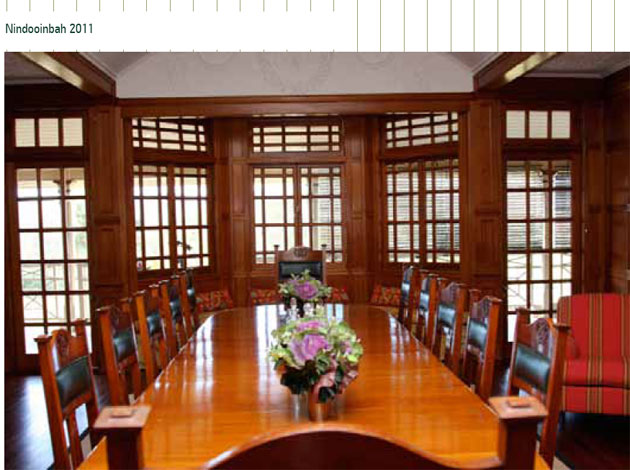

Some other elements of the original verandahs can be seen reused as floor and verandah framing. The work was completed by 1908 judging by the date incorporated into the plaster decoration in the dining room ceiling. The dining room itself is without parallel as an example of Dods’ interior work in an Arts and Crafts manner. In fact it would be difficult to find a better example in Australia of its type. Its vaulted plaster ceiling, sparingly modelled with enrichment is combined with silky oak panelling and built in furniture, and a secretly nailed hardwood floor. The chimney piece in sandstone and glazed tiling combine with the other elements including distinctive joinery to the bay windows to produce a room relying on minimal finishes and superior workmanship. The inscription over the fireplace is totally in keeping with its English or Scottish origins:

‘The garden is gay in the month of May the fire the flower of a winters day.’

One can see parallels here with the work of Sir Robert Lorimer, who was considered the finest Scots architect of his day and who was a close friend of Dods. The dining room had a built-in sideboard within the western bay window and an upholstered seat within the eastern bay. The windows here have particularly heavy and additional transoms with many small panes of glass. The stain glass patterns on the west side were simplified from the detail shown on Dods’ drawings, in fact a rather ordinary green patterned glass was used. In addition, a china cabinet was concealed behind the panelling, which helped distinguish this house as very up to date. What is important about the design of this room is that no finishes were used to disguise the nature of its materials. The plaster was left unpainted and the panelling was left raw. The floor of Red Stringybark had only a beeswax polish. The stone too was left natural all of which was consistent with an Arts & Crafts approach. The dining room suite, while not to Dods design is still a valuable addition to this room and has survived.

The house in its enlarged form was indeed a superior specimen of its type. Dods replaced the timber shingles of the old homestead with corrugated iron and introduced a slatted soffit to the verandah edge, which allowed increased cross ventilation. The additions also included ventilation openings in the 3 gables of the western elevation to supplement 2 more traditional iron ventilators on the ridge. On this house there was no horizontal ventilated ridge as found on almost all of Dods other houses with iron roofs.

The gables on the western elevation form an important part of the design. To equalise the width of the 2 wings of which the bedroom side was the greater, a double gable was used on that side. This offbeat symmetry was typical of Dods and can be seen also in the garden front and its relationship with the avenue of palms centred on the northern most staircases rather than on the central gable.

Unlike most other houses by Dods, this project made extensive use of wallpaper. Wallpaper was commonly used in Queensland homes and was readily available through a number of local suppliers. Wallpaper had been used in the early house also. The specification notes that walls in the added 1908 rooms were to be sheeted in flush 6” boards to which hessian was attached ready for wallpaper. In all, 11 rooms were wallpapered and the ceilings and frieze were included in most.

Much of the wallpaper is in poor condition (I would argue its condition; while it is poor compared to new papers, it is good compared to papers of a similar age which survive insitu) having suffered from acid attack through the hessian and timber boarding to which it has been fixed. The most significant paper is in the drawing room and in the guest room. The floor coverings, wallpaper and window furnishings are discussed in a separate report.

There were a number of differences between what was shown on Dods’ drawings and what was actually built. This was not unusual as changes were often made during construction. It nevertheless needs comment. The drawings show a large central stair to the eastern (garden) front whereas twin staircases symmetrical about the centre gable were in fact used and a parterre type garden bed, heart shaped, was on axis with the stair closest to the drawing room. This was a more complex idea than as shown on the drawings and replicated the position of the earlier 1858 stair. It also worked better to have the stairs either side of the gable that was added central to this elevation.

The service wing was lengthened from that drawn to bring it level with the bedroom wing. This involved some planning changes. An important part of the design was the ceremonial entrance path beneath a substantial pergola with a grapevine growing over it. This element terminated with a balustraded porch decorated with a low parapet balustrade around its roof. Although it no longer survives, this element was built as drawn, and it appears in photographs after the work was completed. The porch was later enlarged to make it suitable for dancing and the posts reused. The new building while lacking the finesse of its predecessor still has significance in that it marked the visit of the Prince of Wales who famously, failed to appear in July 1920, choosing instead to visit the nearby property of ‘Coochin Coochin’.

Another addition likely to have been carried out at this time is a delightful corner bathroom in the form of a 5 sided bay window, Ensuite to the best bedroom. Its painted panelled walls and continuous sash windows and fittings make it an extraordinary survivor of the period. The most significant rooms are in the garden front part of the house and include the best bedroom with its Ensuite, the drawing room, the telephone room or former entrance hall, the dining room and the guest bedroom. The guest bedroom adjacent to the dining room was included in the 1908 work. According to Philip Cox a large Bunya pine was felled to extend the house at this point and Dods suggested that the timber be used to turn into furniture for the room. This was apparently done and included was the chimney piece also of Bunya pine. The furniture was probably not designed by Dods although the chimney piece may well have been. This room is considered to be the next most significant room in the house after the dining room and contains a complete decorative scheme. Adjoining the guest room are the bathroom facilities for guests including bathroom and separate ladies and gents toilets.

The 1920 ballroom which replaced the 1908 porch is again of considerable significance. In the absence of any documentation of its design it would seem that the integrity of its enclosure is suspect. It was either hastily conceived or has had a series of repairs as it lacks the attention to detail apparent in the rest of the work. Dods was not part of this later work as he left Brisbane in 1913, dissolved his partnership with Hall in 1916 and died in 1920. The homestead as a whole is a stunning example of its type as well as being one of Dods best works. Dods work is highly regarded but few houses have survived in anything like the way they were designed or built.

The bedrooms in the north wing and the kitchen and servant rooms in the south complete an impressive and clear plan surrounded by generous verandahs. There are flyscreen doors to most rooms and a flyscreened enclosure to both verandahs outside the best bedroom. Of course the homestead is the largest of a group of buildings on the site which when included with the outbuildings and other houses amounted to almost a village.

The homestead has been home to three generations of the same family being that of William Collins (1846 – 1909) and his wife Gwendoline. Although William lived in the house for less than a year after its completion. Gwendoline stayed on until her daughter, Beryl married Robert de Burgh Persse in 1938. Even then Gwendoline had the best bedroom set aside for herself until her death in 1962.

Beryl Persse also outlived her husband and stayed in the house until her death in 1982. Her daughter Margaret married Patrick Hockey in 1983 and outlived him until dying of cancer in 2004.

The story of Nindooinbah is much related to these 3 women and the wealth that enabled the place to be established to such a high standard and its gradual decline thereafter.

Nindooinbah is a private house, not a museum. However, it is rare for wallpapers, carpets and window furnishings to survive for almost a century as elements of what was once a rich and diverse collection. Although not a museum, the relationship between the surviving items and the building in which they are located is strong. They provided a backdrop for the furniture, fixtures and furnishings throughout the house, and give insight into the decorative inclinations, social status and style of the family, the architect and early 20th century society in general. They provide information about the design intent of the architect, Robin Dods, and although it is not known whether he personally selected the decorative elements, he specified that the walls were to be prepared for paper, specifying costs and, therefore, quality of the wallpapers, and dictating to some extent the arrangement of the papers by placement of items such as picture rails. The finishes allow the rooms to be ‘read’, providing information about social conventions of the Edwardian period by affirming the hierarchical pattern of room usage.

Nindooinbah sits in a valley overlooking a lagoon, fl at alluvial land, the Albert River and mountain ranges. This drama of this setting is enhanced by the sense of anticipation engendered by the approach to Nindooinbah via Nindooinbah House Road which offers significant views, and by the driveway to the house which contributes to the sense of entry to a private world.